- Home

- Miklós Vámos

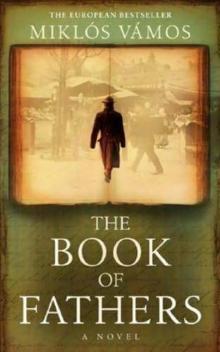

The Book of Fathers Page 8

The Book of Fathers Read online

Page 8

Bálint Sternovszky was due to sing the third, the fifth, and the closing numbers. Helping hands had provided him with a music stand, though he had no need of such. When the time came, he stepped up to the stand and waited for the maestro’s signal after the opening bars. Other singers would at this point be floating on the surface of the tune, ready to begin; Bálint Sternovszky knew that when the moment came, there would issue flawlessly from his mouth, in a single movement, all that he had inherited. He thus had time to look around. He saw the flushed cheeks of the ladies, the fluttering fans, the ceaseless play of the candlelight, the bored expressions on the faces of the liveried servants propping up the walls, enjoying a moment of relaxation.

His mouth was just rounding out into the opening sound when he turned pale and froze. The maestro knew that the bars would recur and gestured again, but for Bálint Sternovszky nothing existed any more except the snow-white face, the dark eyes, the dark hair combed into a chignon. In his numbness he was unable to move and so could not run and fall on his knees before her. Meanwhile the maestro had told himself a hundred times that he should not have had anything to do with this madman of the turret; you should never have dealings with eccentrics and odd men, he knew that, but needs must. He was furious with the dean for embroiling him in this farce. No use crying over spilled milk. Heavens, it could cost him his job. Head bowed, he continued to play; the players bore up well, and even without the song the piece billowed its way to an affecting climax.

Bálint Sternosznky had no other role in the first half of the performance that evening. At the interval the maestro turned on him with a face like death: “What on earth was that?”

Sternovszky walked off without a word, as if in a dream, towards the creature whose very sight had blotted out all. The maestro did not follow, but hurried over to Count Forgách and bowed deeply: “I earnestly beg your grace’s pardon for this deeply embarrassing episode with his honor Bálint Sternovszky. I have no idea what got into him.”

The Count’s consumption of punch had been sufficient for him to take a lenient view of the business, and with something of a grin he said: “Well, we managed to survive, what? The others labored tolerably well, wouldn’t you say?”

Nods and approving noises from his circle.

“Next time organize a woman to sing, eh?” the Count added.

The maestro again bowed deeply and hurried back to his players. “Where on earth am I going to get a woman?” he steamed. “They are as rare as hen’s teeth.”

During this time Bálint Sternovszky hunted high and low for Kata Farkas, but without success. He kept the distance of a bargepole from his wife and two sons. People whispered behind his back, some thinking he had gone unexpectedly hoarse, others suspecting he had succumbed to witchcraft. There were already rumors aplenty in the county about the noble who lived in the turret. Bálint Sternovszky offered no excuses or explanations, but for the second half of the concert did not take his place with the players. He hovered at the back by one of the doorways, scanning the audience with mounting agitation. Kata Farkas had disappeared into thin air. Bálint Sternovszky felt he was losing his mind. He was shivering, and sweating so much that damp patches began to form on his clothing. He now perceived the world around him only in broad outline. He could hardly control the trembling of his knees or maintain himself upright. He slid down the wall and onto the highly polished floor.

Two servants standing nearby pulled him unobtrusively out into the corridor, where they brought him back to consciousness with a glass of plum brandy, and then helped him to his room. As he recovered he asked them where the lady Kata Farkas had been seated. He was informed that no guest bearing this name was to be found anywhere in the castle. Some while later his wife and boys asked to be admitted but he turned them away, saying he felt too weak. It was no lie: his fiasco had distressed him just as much as had the sudden sight of Kata Farkas. Though now he was no longer sure that he had really seen her.

Mrs. Emil Murányi had been lodged in two interconnecting rooms with her husband and three little daughters, of whom the youngest, Hajnalka, was a source of continued concern, beginning with her birth, when the umbilical cord had wound itself around her neck and would have strangled her had the midwife not managed carefully to untangle it. By the time she did so, the newborn had turned as blue as a forget-me-not.

“Lord a-mercy,” the mother whispered, “will she live?” The midwife gave no reply, splashing the newborn baby who had, worryingly, not yet uttered a sound, with warm water. To cap it all, the baby’s left eye was sky-blue but her right corn-yellow, and this perhaps betokened some illness. Within a day or two, however, Hajnalka Murányi had picked up and was cheerfully sucking away at her mother’s breast, behaving in every respect as any other child of her age. But once a month, quite unpredictably, she would have an attack: she had trouble breathing, bubbles foamed from her mouth, her skin turned as blue as at birth, she thrashed about with her limbs, or lost consciousness, and for short periods her heartbeat would also fail. At such times they would send the maid running for the doctor quite in vain: invariably, by the time he arrived Hajnalka was happily sucking her thumb with a peaceful smile and quite unaware of the panic that she had induced in those around her. Mrs. Murányi never traveled anywhere without Dr. Koch: better safe than sorry.

She was not minded to accept Count Forgách’s very kind invitation. Her children were still too small to be going to balls and concerts. Emil Murányi thought otherwise: one had to get out of these four walls sometimes, and Count Forgách might take it amiss if they declined. Naturally they would take Dr. Koch with them: there would be no worry on that account.

At the eleventh hour Emil Murányi received bad news: Your father has had a stroke, wrote his mother, and has no movement in the left side of his body; come at once! So he could not join them in the carriage. Before galloping off on his black steed, he promised to meet them at Castle Forgách the next day, if at all possible. Mrs. Murányi had a feeling that this little trip would not pass off without incident and made sure Dr. Koch brought with him the entire contents of his medicine chest. Her foreboding was fulfilled some one-third of the way through the concert, when Hajnalka’s eyes swelled up and her breathing became labored and turned into a hiss. As she began to froth at the mouth, her mother and Dr. Koch bundled her up and made a dash for their room, where they put her to bed, placed a bandage on her forehead, and held down her arms and legs to stop her doing herself an injury.

“We have caught it in time, madam,” whispered Dr. Koch, as the girl’s steadied breathing showed that the danger was over.

“God be praised.”

Mrs. Murányi would not have been unhappy to have her husband burst into the room. She knew hardly any of the guests, and hated nothing more than to be the focus of attention in strange company. She thought all eyes were on her as they ran from the sala grande with the limp little body; her cheeks were crimson with embarrassment and the excitement of the day. On these occasions her husband always knew how to calm her down with soothing words and the broad, cool palms of his hands. Emil Murányi was always the subject of somewhat condescending smiles for the slowness of his speech, which was almost a stutter. Born with a harelip, he was able to disguise this with a lavish growth of facial hair, but the manner of his speech gave the game away. Kata was quite untroubled by this; with no other man did she feel so completely safe, including her own father. Emil Murányi held some 90 Hungarian acres of land, of which he took exemplary care; people came from far and wide to admire it. His estate manager was a Saxon, who had the hayricks constructed in the cylindrical style of his homeland; this was enough for an expert eye to tell that the lands belonged to Emil Murányi.

Dr. Koch’s room was in one of the castle’s outbuildings, with those of the other guests’ servants. He kissed Kata’s hands as he left: “I cannot imagine that there will be any problems, but if you need me, just send!”

As soon as she was on her own, Kata removed her ballgo

wn. Despite her husband’s protestations she did not want to bring her maid for just the one night; she was quite able to undress by herself. Had she worn a corset, she might well have needed assistance, but she had not. She put on her silk dressing gown and red slippers, sat down in the armchair and listened to the music filtering through the half-open window. The concert was over, and there remained only a Gypsy band giving its all on the terrace. Kata closed her eyes. This music reminded her of her childhood, when her father woke her daily with the sound of the violin. He had knelt by her bed, the instrument lodged firmly under his chin, and the melody came meltingly from the strings as her father crooned the words: “Wake up, sleepy head, sunshine’s on your bed…” This was the most wonderful thing he ever did for his daughter. Though Kata’s husband did not serenade her or the children with such morning music, in every other respect he was a better man. She forced herself not to think of her father’s sad end, but of her husband’s face instead. I’ll croon for two. If only Emil were here!

There was a timid knock.

“Yes?” she said, making for the door with a spring in her step.

From the opposite direction there came: “Please, don’t be frightened, I’m… it’s… I’m…”

A dark shape framed by the glass of the window. Mrs. Murányi let out a scream.

“Don’t… forgive me for… do you not recognize me?”

The woman shook her head. She picked up the candlestick and took a step towards the door. But she now knew, even without the light. She had seen the name of Bálint Sternovszky in the program and was surprised that he was singing here; she was curious and somewhat concerned about how it would feel to see him again. But Hajnalka’s fit had driven all of this out of her head. “You are incorrigible! Haven’t you heard about doors?”

Bálint Sternovszky eased himself into the room. “I know… I am lodged two rooms away… I had only to climb over the balconies and… you haven’t changed at all!” A beatific smile lit up his face. She looked exactly as she had all those years ago, in the loft room of Kata Farkas.

“Please don’t!” Kata had no illusions about the ravages of having given birth, which her silk dressing gown generously shielded from view. She was twenty-eight Viennese pounds heavier than when she married. It did not bother Emil, who often said you cannot have too much of a good thing-or a good person. “But you have indeed not changed at all,” she lied. The vast amounts of hair had transformed Bálint from a boisterous puppy into a suspicious hedgehog. “Nonetheless, I must insist that you leave. It is not done to burst into the room of a married woman under the cover of night.”

“It’s still only evening,” mumbled Bálint Sternovszky.

“Leave at once! Or I shall scream!”

“I beseech you, please, don’t scream, not a finger will I lay on you, all I beg of you is that you hear me out!”

Kata could not help but smile. The words were deeply etched in her memory. She responded with another quotation: “Hurry and say your piece, then out, before they catch you here!”

Bálint Sternovszky gave a little sigh of relief and bowed as he knelt. In the years since that scene, the scene that Imre Farkas II’s bursting into the room had shattered, had flashed before him a thousand times. A thousand times he had rehearsed all that he could have said to Kata to soften her heart towards him. He had even thought up clever words he could have said to blunt the anger of her enraged father, instead of scurrying away with his puppy tail between his legs. Every time he thought of these things he came to the conclusion that it was no use lamenting the past. He had never imagined that another occasion would arise when he could be with Kata, years later, a scene lit only by candlelight and the twin stars of Kata’s eyes, just as it had been then.

I’m not going to get it wrong this time! He could hear the sound of loud cracking and realized it was his fingers. Come on! Out with it! But the words would not come.

The marble paving of the corridor floor resounded to steps that suddenly they could both hear: metal-heeled riding boots neared rhythmically. “Surely, it can’t be…” thought Bálint Sternovszky. Kata’s father had long ago ended his days in the main square of Felvincz.

There was a knock. Kata shivered and firmly pushed him in the direction of the window.

“Kata, my dearest!” said a velvety voice in the corridor.

“Emil! How wonderful! I’m coming!” she said loudly, but pushed the window wide open. Her eyes commanded him with such steel that he obediently stepped out onto the parapet.

“No, it can’t happen again, just like last time, no, please, no!” he thought in desperation. If they caught him like last time, Kata would hate him forever, to say nothing of the scandal, the duel… He readied himself to swing over the wrought-iron railings of the balcony next door.

The nighttime dew had wetted the metal rail and he slipped, latching on to the wooden shutter with his left hand as his right arm desperately reached out for something-anything, and then he fell, at first upright but then head-first onto the ground. An almighty thud as he struck, his back cracking on the stone flags of the pathway around the building. Complete darkness.

Slowly the mists cleared. Up above, the light of a few square windows shimmered in the dark. Here and there candles were lit, heads turned towards him from every direction. He sought only Kata’s face, an apologetic smile planted on his own, but Kata was nowhere to be seen. From down here he was not entirely sure which window he had fallen from, so he could not pick out Emil Murányi from the many men blinking at him incredulously, unable to comprehend what he was doing down there, with his body and limbs in such a curiously twisted shape.

The pain came only later, by which time the world had turned gray and images and sounds were fragmenting into smaller pieces. Behind his brow the many ancient faces began to stream forth; scenes, landscapes, time rolled backwards for him, the torrent of images seemed as if it would never end.

First on the scene was manager Bodó, lantern in hand. He clapped a palm to his face when he saw the twisted body. Is there never going to be a moment’s peace in this accursed estate? What on earth has happened to this man? Is it not enough for him that he came to grief at the concert? What a mess! He hunkered down and touched him on the shoulder. Then he saw that the grass was red with blood. “Holy Mother of God!” he said, straightening up. “Get Dr. Kalászy! At once!”

Dr. Kalászy had, however, consumed so much alcohol at dinner that there was no reply when they hammered on his door, except the sound of a rasping snore. But Dr. Koch hurried over on his own initiative, a cape thrown over his long nightshirt and a capacious doctor’s bag under one arm. A brief examination later he whispered into the manager’s ear: “Summon a priest.”

By then Borbála had arrived, weeping and moaning, throwing herself on the body of Bálint Sternovszky, who thought that this was the last straw and that he must die. The gut-wrenching shrieks of the woman could be heard far away. “Oh, dear husband, sweet husband, do not leave us, my dearest, don’t do this to us, oh my God, please save him!”

Count Forgách arrived just as manager Bodó was having an unused bed frame brought over to serve as an emergency stretcher, onto which his men heaved the massive body. Just like a peasant, thought Count Forgách, then, out loud: “What has happened here?”

“He fell out of a window.”

“Oh my dear husband, what will become of us without you?” wailed Borbála.

Dr. Koch’s efforts to drag her from the body of her husband were in vain. It needed two people to grasp her by the arms and take her to one side. Bálint Sternovszky was quickly taken to a sheltered spot. At this juncture the Count realized that the victim of the accident was the singer who had failed to sing. I should check with the estate manager if he has paid him yet for the performance-he certainly does not deserve anything.

The body was carried to the small house in the garden, so that they did not have to brave the throng. Dr. Koch kept feeling for Bálint Sternovszky’s pulse, listen

ing to his heart, but he felt and heard nothing to make him change his mind, and when Borbála was not looking, he shook his head in response to manager Bodó’s questioning glance. However, Bálint Sternovszky clung on: a movement of his leg or a twitching eyelid gave notice that he was still alive. Borbála clutched his hands encouragingly (something he could not feel as he teetered on the brink of death). An acidic pain throbbed in his head, cascaded into his chest, bludgeoned every part of his body.

He saw, as of old, as in Kata’s loft room, times past. First it was stations in the life of his father and then of his father’s father and, beyond that, his great-grandfather. He sensed these might be his final hours and that he was seeing the images for the last time, unable to do anything about them. He regretted that he had spent his years in such sloth and without purpose. For the thousandth time he realized that he had been the cause of his father’s premature death, something for which he could never forgive himself. And now came the painful realization that he had deprived his own brothers of something that perhaps, though they did not know of it, rightly belonged to them also. It makes no difference now.

He had spent most of his time without noticing its passing: lolling about, singing, in the self-satisfied manner of a married man, doing nothing, enjoying being served and enjoying that he did not have to serve. God! Why did I not make more of an effort? Why did I not pass on to my sons the knowledge I managed to glean? I could have written it all down in the folio from my father, had I thought about my offspring. Yet I only made notes on music. How selfishly I have lived! It’s all too late now.

The Book of Fathers

The Book of Fathers